What do young people think of radicalization in the ecology field?

Since researchers (S. la Branche, 2019; E. Gravier & S. la Branche 2020) claim to have identified a certain tendency towards the radicalization of young people in the ecological movement. We have collected activists points’ of view on this subject during our survey. Without asking them to define radicalization directly, we asked them, amongst other things, what they consider to be a “radical person”, a “radical opinion” and a “radical action”.

The answers provided by the young interlocutors to these questions, as well as those relating to the reasons for radicalization, make it a process during which a person passes, in his convictions and actions, from stage A to B:

- Stage A: moderation in beliefs and actions, openness to contrary ideas, adversity without excess;

- Stage B: rigidity in beliefs and closure to contrary ideas, lack of moderation in actions that are sometimes illegal or even violent.

The answers of the young people we met, overlap with general definitions of radicalization, including that of C. Guibet Lafaye (2017) who equates it with a “total” commitment as it consists of “committing one’s life”, “going all the way” and “means taking action” over time through radical actions.

Starting from the nature of the positions and the repertoire of actions, Isabelle Sommier (2012: 15) uses the concept of radicalization to characterize the engagements which, “from a posture of rupture in regard to the society of membership, accept at least in theory the use of unconventional forms of political action that may be illegal or even violent”.

The characteristics of radicalization according to the young people interviewed

1. Acts and opinions perceived as excessive and extreme

According to our respondents, the process of ecological radicalization results in a tendency to commit and take positions that an external view often perceives as excessive, extreme or even violent; whereas the activist concerned can accept them and/or justify them by various arguments relating to the importance he places on the “ecological crisis”.

Read more…

In addition, respondents to our survey associate radicalism in ecological engagement with positions that reflect a tendency to believe that they hold “the only” truth on the question of ecology. Therefore, it involves closing oneself off from any contrary ideas or opinions, no matter how sensible.

Words from young people…

“For me, a radical person is a person who is persuaded that they hold the truth and who would go all out in their thing without ever listening to anyone, even the people who care about them and who want to help them move forward, who wants to go all out, including doing things that are sometimes counterproductive. For me, someone radical, really radical, is just someone who is convinced of having the truth and then who wants to go all out in their thing without listening to anyone.”

André, 23 years old, eco-engaged

2. Actions and opinions perceived as violent

Respondents see radicalism through certain opinions and actions (sometimes both) that can be psychological, symbolic, physical or material attacks in the name of the ecological cause.

Read more…

In our survey, our respondents speak little of “taking action” and do not validate physical violence against humans. They are, as such, a reflection of the French ecological movement, barely scarred by attacks aimed at assaulting the physical integrity of people. In addition, the idea that radicalism in ecology leads to being closed to “discussion” must be qualified. What must be said is rather that they are closed to the idea of allowing themselves to be convinced on the basis of ideas contrary to those which they consider unalterable since they are scientifical. Finally, the activists we met are working to convince citizens to adopt more eco-responsible behaviours even if, from this perspective, they tend to impose or validate the idea that more restrictive ecological measures can be imposed on the whole of society.

Words from young people…

“For example, a radical opinion would be to say that, as we know that meat pollutes, we should ban the consumption of meat, but in my opinion this is radical because it deprives people of their personal freedom which is the freedom to eat whatever they want. […] For me, radicalism, in terms of the ecological fight, it will really start to happen with civil disobedience, but civil disobedience for example with XR which will block congresses, which will block airports, create ZAD (zone to defend), that for me is radicalism. And there are certain radical ideas […] which for me are too violent, for example, going to picket a slaughterhouse to prevent animals from being killed”.

Leyla, 16, Youth For Climate

“For me, a radical person is a person who would be persuaded that they hold the truth and who would go all out in their thing without ever listening to anyone, even the people who care about them and who want to help them move forward, who wants to go all out, including doing things that are sometimes counterproductive. For me, someone radical, really radical, is just someone who is convinced of having the truth and then who wants to go all out in their thing without listening to anyone”.

André, 23 ans, éco-engagé

What motivates radicalization according to our respondents

In your opinion, what can lead an eco-engaged person to move towards radicality? Our survey has highlighted two elements that may, for some, explain the radicalization of opinions and/or actions:

1. Awareness of the scale of the environmental crisis

Many of our respondents explain radicalism through awareness, not only of the urgency of the situation, but also of the scale of the disasters unfolding right now.

Read more…

Following a wake-up call, radicalism sets in, according to respondents, gradually with individual and then collective actions, through which the individual opposes “social norms – and in particular [the] social habitus linked to consumption – in effect” (E. Gravier and S. La Branche, 2020)”.

Thus, most interviewees see radicalization as a “wake-up call” to the magnitude of the “ecological problem”. Note, moreover, that one can become aware of environmental issues without getting involved, just as one can get involved without becoming radicalized.

Words from young people…

“It makes me want to be more radical, precisely because I feel more and more powerless and suddenly I have more and more the impression that when we campaign for people to become vegetarian, for example, I see less and less the point of doing that, and in addition the health crisis really makes us realize that everything can stop overnight and that in fact it makes us want to use our energy better, I don’t know actually, well I don’t want to do useless things because I feel the urgency of the thing even more. […] Precisely, well, I don’t know, in fact I don’t have an example because I don’t know what to do; I feel like what we should do is just take over ourselves, but that seems way too big of a thing to me, it seems too complicated to me, and the things that I feel capable of doing, I feel like they’re unnecessary, so I’m kind of in between, well the things that I think are radical enough and effective enough are too complicated and the things that I think are doable aren’t effective enough.”

Anissa, 19 years old, eco-engaged

2. Feelings of helplessness in the face of the ecological situation

Our respondents recognize the ineffectiveness of some of their actions regarding the ecological situation. On the one hand, they explain that eco-gestures and collective actions such as peaceful protests have little impact on society. On the other hand, it is impossible for them to take political power to impose laws on industrialists and put an end to consumerism. It seems that this awareness of the limits of engagement determines the radicalization of certain activists.

Read more…

Many of our eco-engaged respondents and even those opposed to ecological activism share the idea that radicalization passes or implies a rupture with certain consumption practices and certain uses. The example of veganism came up in many speeches as an indicator of radicality. Being or becoming vegan or vegetarian accompanies the journey of the environmental activist. These practices become the symbol of respect for animal life which has the same importance, if not more, as human life. The rejection of certain means of transport such as planes and cars is only associated with radicalization by very few eco-activists. Finally, it is mainly the external gaze that associates these acts with radicalism. Eco-gestures are the sign of an ecological engagement, they can be considered radical (such as veganism, rejecting planes, etc.), or more ordinary (such as the selective sorting of waste). However, they do not determine radicalization and do not explicitly define radicality.

Words from young people…

“[…] eco-gestures, etc., that’s good, but that’s not the only thing that can change things. But I think it’s already better than what the government and companies are doing. Because at least the citizens are doing something and they are trying for their part, even if it is a bit of a helpless way of doing something; because we know that it’s not going to change everything, but I think it’s a good start. […] We at Youth For Climate, for example, try to act by taking part in acts of civil disobedience, by protesting, by being a part of local struggles, etc., and I already find that a little better. But, we know that we are trying to do a lot of things and that we are not having a huge impact because companies and the government have the power to change things completely.”

Marie, 18 years old, eco-engaged

All eco-engaged activists who lean towards radicalism validate the idea that citizen actions should increase in intensity. On the one hand, they aim to force governments and industrial polluters to change policies and production methods. On the other hand, they want to impose more eco-responsible behaviours (beyond selective sorting) on populations. According to Bertrand (19), one of our eco-engaged respondents, to become radicalized is “to want to deconstruct the current system because it does not correspond to ecological realities”.

Is violence justified when one is engaged?

In your opinion, is there a limit in the intensity of the engagement? Is physical violence necessary in the ecological struggle? In our quantitative survey, we wanted to know what proportion of the French population would be willing to sacrifice their future or that of their loved ones to defend the environment. The statistics obtained on certain indicators of radicalization allow us to situate young people on this subject in France.

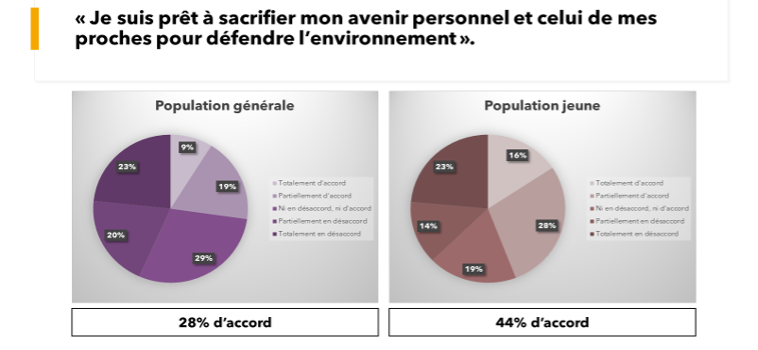

Sacrificing your future for the environment

Pie chart: “I am willing to sacrifice my personal future and that of my loved ones to defend the environment”.

Analysis

28% of all French people compared to 44% of young people aged 15-24 say they are ready to sacrifice their future and that of their loved ones to serve the environmental cause. The high proportion of young people who would make such a sacrifice is consistent, on the one hand, with the gloomy outlook that they mostly express in our qualitative survey, about climate future and, on the other hand, with the fact that 59% feel “partly responsible for the state of the planet”. For example, Esté, who responded to our qualitative survey, wondered about a future that she reduced to the scale of a human life by saying “we don’t know if we will be alive in France in 2050 for example”. (Esté, 17 years old, eco-engaged)

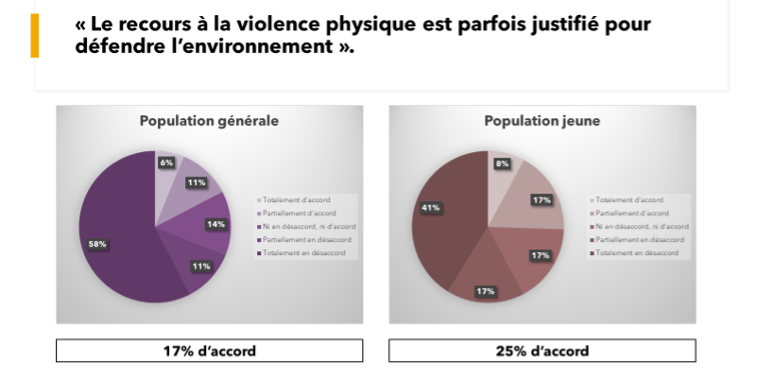

Using violence for the environment

Pie chart: “Using physical violence is sometimes justified to defend the environment”.

Analysis

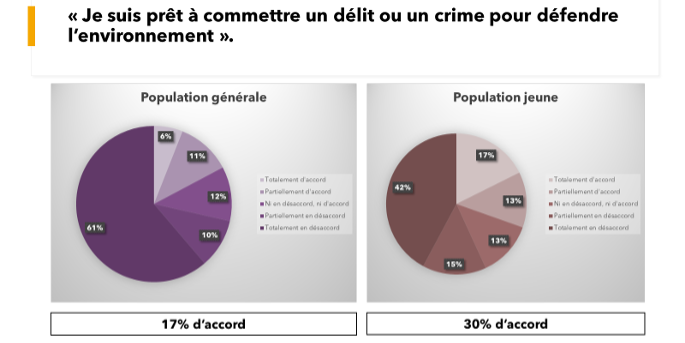

Breaking the law for the environment

Pie chart: “I am willing to commit an infraction or a crime to defend the environment”.

Analysis

We also polled the French on the idea of committing an offence or crime in the name of the defence of the environment. The finding is that the trends confirm those relating to the idea that “physical violence is sometimes justified” for the same cause. Our quantitative study therefore teaches us that violence can, for some, be justified when it comes to the future of the planet. What we can retain here is that the people involved do not all have the same limits in terms of the actions to be implemented to protect the environment. Some people are ready to put their future at risk to defend the environment, to use violence or to commit an offence or a crime, while others do not wish to resort to this type of action in any way. This shows us that the ecological movement is beset with different positions on this subject.

Pour aller plus loin

- Gravier, E., La Branche, S. (2020) « Les jeunes en voie de radicalisation écologique ? Critères d’identification et d’identité ». La pensée écologique. Online here

- La Branche, S. (2019) « Écologie politique des étudiants d’université : vers une radicalisation ? ». La pensée écologique. Online here

- Guibet Lafaye, C. (2017) « Engagement radical, extrême ou violent, Basculement ou “continuation de soi ?” ». Sens public. Online here

- Sommier, I. (2012) « Engagement radical, désengagement et déradicalisation. Continuum et lignes de fracture ». Lien social et Politiques, (68), pp. 15-35. Online here